“Didja feel that?”

Something had just lightly smacked the roof of the truck as it bounced down some New Mexico highway or another.

“That’s one of the elders taking the form of an eagle, letting us know we’re clear to travel here. They’ve taken the energy barriers down,” Leland bellowed from the front seat before I answered. His fourth and final wife, a former actress of stage and screen named Carmen, nodded in enthusiastic agreement. These sorts of explanations and odd statements were characteristic of my late father.

I was a goofy, nerdy, awkward, emotional, open-minded, “spiritual but not religious,” bright but impressionable Canadian boy who had traveled to the United States as an unaccompanied minor to get to know my American father and to finally see my place of birth. I was coming of age and celebrating my 13th birthday in New Mexico in lieu of a formal bar mitzvah, born into Jewishness via my Ashkenazi mother.

I was raised in Canada, a secular Jew but in practice was a “Religious Scientist”, attending weekly “we don’t call it a church” Sunday services and I was open to a wide variety of spiritual ideas which I only later in adulthood accepted to be a jumble of Western pseudoscience, occult, and culturally appropriative mixed Asian and indigenous North American philosophy. My mother and father were both entrenched in variations of new age belief and practice prior to and throughout my childhood, and had originally met in the late 1970s through a new age spiritualist organization called the Inner Peace Movement. After the two parted ways in my infancy, my mother brought me back to her hometown of Calgary.

I have vague memories of visiting my father and some of my American family in my early childhood, though memories are fuzzy and I’m never quite sure which images draw from my own experiences and which are more recent memories of photographs. In truth, my memories are probably a composite of both. I was raised to understand that, in spite of distance and the reality that it could never work out between he and my mother, Leland still loved me. That didn’t prevent his name from being used as a threat from time to time, as is apparently common in single-parent, maternal households — being sent to live with my father was a scary thought to a child who had never really known him. I never called him “Dad” and referred to him always by his first name only. Even saying “my father” is a more recent development for me.

As I grew older and heard more of the story, it became clearer why my parents had parted ways. In my early years the two had traveled the US performing “spiritual work” such as psychic readings, energy healing, and psychometry. While my mother has strong self-preservation instincts and was always fiercely protective of her children, this was less the case for my father who was inclined to leverage what he viewed as enhanced insight in very public ways, going as far as confrontation with those who would have none of it. He traveled a lot as I grew up, and on each rare occasion he visited or we would speak on the phone he would be living in a new place. What I gleaned from hushed voices as he and my mother spoke was that he occasionally ended up in sour business arrangements leading to disputes with rough individuals and possibly the government over money.

In 1994, at the time of my trip, Leland was back to living in my birthplace of Albuquerque, New Mexico. While settled for a time, I learned on my visit that he still viewed himself as under threat from folks he had pissed off elsewhere. Both he and Carmen were concealed firearms carriers, a concept completely foreign to me as a Canadian. He offered to take me to the range during my two week stay, an offer I declined primarily out of fear at that age — I’d inherited my mother’s self-preservation instincts, though in my adulthood I’d later spend some time as a target shooter in possession of my own pistol.

Over the two weeks I saw much of New Mexico and a bit of Arizona as well. To say Leland was an enthusiast about Native American culture and history is to put it very lightly. He knew much about the Anasazi, and the modern day Hopi and Navajo people. During my visit, he spoke often of his indigenous friends (some of whom, I was told, were spirits rather than currently living people) and one afternoon we shared tea with a Hopi elder who gifted me a beautiful carved tortoise I still have to this day. He was not indigenous himself, and while he clearly spent time with many indigenous people throughout his life, his own views and practices were a mishmash of world beliefs, especially those of more “exotic” cultures. During my stay I saw the caves and structures of the Ancestral Puebloans, camped out under the stars at Window Rock in the Navajo Nation, and saw the collapsed structures of oppressive Spanish colonists. I treasure these experiences shared with my father and his wife over those two weeks.

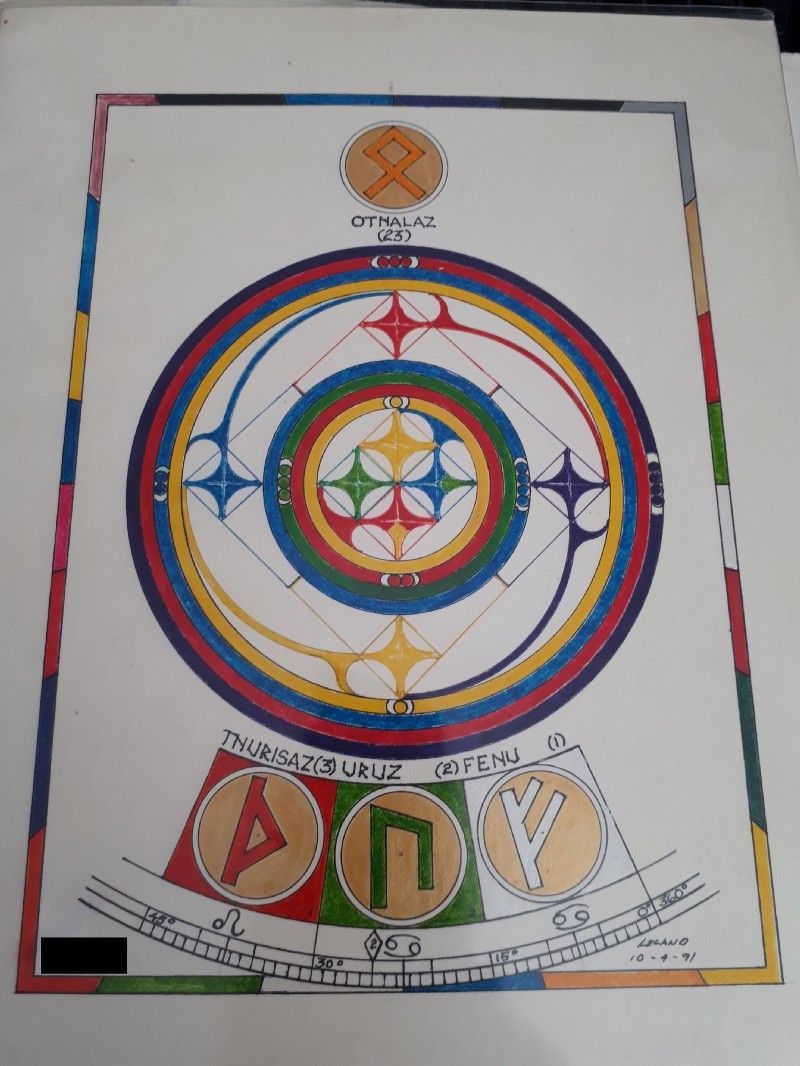

Leland thought very highly of himself, believing himself to be doing critical “energy work” on behalf of alien spirits — like himself, as he believed his own soul and, conveniently, the souls of those close to him to have originated in a galaxy far from our own — to keep the planet’s “energy fields” in alignment. He enjoyed geometric design which he put to use in a practice of creating strange runic charts of peoples’ souls and mapping the energies of the planet. His wife, Carmen, participated with him in some of these efforts. At odd times during my stay, he would roll his eyes back in his skull and engage in one-sided dialogues with “spirits”. To this day I’m still not sure if this performance was the embodiment of his own schizophrenic thoughts (though, to my knowledge, he had never been formally diagnosed) or an act to convince me and others around him of his authenticity, but it was at once believable, awesome, and a little bit frightening to a now 13 year old child who had been raised to believe in invisible spiritual forces governing our world. It was frightening in the way that spiritual commitment of that magnitude can be frightening, the way I imagine many fear God due to the reverence of trusted others.

Leland read hot flashes as signs of spiritual visitors, momentary breezes as messages; all natural chaos could be explained by an underlying order. Our lives had purpose, the world was an ordered layer of reality, a simulation, maintained for the education of our souls and the balancing of universal energies. Our souls were eternal, their histories stored in the Akashic Records (which was obviously located in Nepal and guarded by yeti) for access by those who were sufficiently “tuned in” to the appropriate energy frequencies, who could project their souls to the secret location. I’d been raised to believe much of this was at least possible, a fantastical story on par with some of the best science fiction and fantasy I’d had exposure to, but Leland was a full embodiment of those beliefs insofar as he was 100% committed to it beyond theory. It was inspiring, frankly, and I took from it a renewed commitment to become as capable as he was of channeling and coming to understand these mysterious forces. Spiritual pursuits guided much of my teenage and young adult life.

I imagine the average reader might think my father was a danger to me. Perhaps I should have felt more threatened, but I was in the fold, a lifelong participant in his vision of the universe, and he was no threat to me. He was simply, as new age folks might put it, “living his truth.” There was no question that he and Carmen cared about me even for as strange as this life must all seem to others.

It took me a long time to process these experiences as I grew older, and longer still to develop a (in my view) healthy skepticism about spirituality and religion as a whole. As ridiculous as these beliefs may sound to most given how rooted they are in new age “shopping cart religion” (thanks to the late Dr. Debra Jensen, my 2004 Religious Studies professor, for that turn of phrase) and concepts we know to be associated with science fiction and fantasy, are they really more fantastical than any other religion, and is faithful adherence to these beliefs really more absurd than that of a fundamentalist devotee to any faith that believes literally in a creator god, fate, destiny, angels, devils, souls, or miracles? Not really. They’re just easier to mock in the extent to which they differ from the mainstream of religious beliefs and practices. All religious beliefs are pretty weird if viewed through an assumption of their fiction and all adherents look pretty similar from the outside.

For all his strangeness, his mixed perspectives, and his distance from me, I found him remarkably accepting of differences in others in the time I knew him. While I hadn’t spoken to him in probably a decade prior to his passing in 2014, he and my mom spoke on the phone occasionally, and I was aware he knew and was accepting of my queerness. I had been told he was the product of a highly regimented upbringing in the 1930s and 40s and, as a soft and creative child, he had been forced by his parents and circumstance at an early age to set aside his artistic interests and get to work. His estrangement from my life gave me the benefit of a cool distance from which to examine his story and I can see how the person he eventually became allowed him an escape from the constraints of a suffocating early life. Leland as I knew him had made himself the hero in his own fiction, a wild west lifestyle of mystery, intrigue, and danger. Snake oil, native appropriation, and white saviours too, but that’s the genre.

Leland’s estrangement is my privilege in some respects — I have only good, if unusual, memories of the time spent with my father. I did not, like several of my siblings, live with the man for an extended time nor can I provide insight into his character prior to my own memories. I have only the stories filtered and shared by my mother, the love I was always told he had for me even at a distance, and the genetics and last name linking me to a large extended family including four wonderful half-siblings. They know little of my childhood and my experience with our shared father, and I know little of their experiences though I have learned enough to know that Leland was far from a model father to them. The image I have is of Leland as the sun having had many others in his orbit along various paths, sometimes bringing us closer to him and sometimes keeping us farther apart, but those who by circumstance or choice orbited too close for too long so often got burned.

At age 37, this is the first father’s day of my adulthood on which I show appreciation for the man who I have often referred to as my “sperm donor”, a distant, larger than life personality who was never a father to me, but who I recognize as a man who, for all the years I knew him from afar, lived true to himself. His influence was felt in my life even over the great distance and silence between us.

RIP Leland Russell Burrell, 1930–2014